There’s a lot we don’t know about the draft, but we do know some important things. That was Part 1.

If we embrace this lack of knowledge and learn the science of making decisions under uncertainty, we can understand how decision making tools like statistical analysis fit into the broader picture. That was Part 2.

That takes us to this third and final part: an example of how to think about the draft through the lens of uncertainty.

Draft Risk Profiles

The history of the draft is clear: we shouldn’t be very confident about our draft projections. So then why do we still talk about prospects as if we know how they’ll turn out? We have strong opinions about which players are better than others. We make comparisons of prospects to established players as if it’s very likely they’ll develop how we expect. We rarely acknowledge that there’s a good chance players don’t end up even sticking in the league.

There’s another way. Instead of oversimplifying, we can discuss prospects with more nuance. We can dig into their strengths and weaknesses, talk about which aspects of the player’s development we are more or less certain about, and debate the value of the player depending on how he develops.

One way to do this more formally is to create what I call “draft risk profiles.” A draft risk profile is based on a few different, broad buckets that players might fall into. For example you might split it like this: All-Star, starter, high end bench player, end of bench player, barely in the league. But how exactly you slice it doesn’t matter — any reasonable division will do. Once we have those buckets we can estimate for any given player what the chance is that we’ll look back at the end of their career and say they largely ended up in one of those buckets. This can help us talk about a player’s value while acknowledging that we are unsure of the outcome.

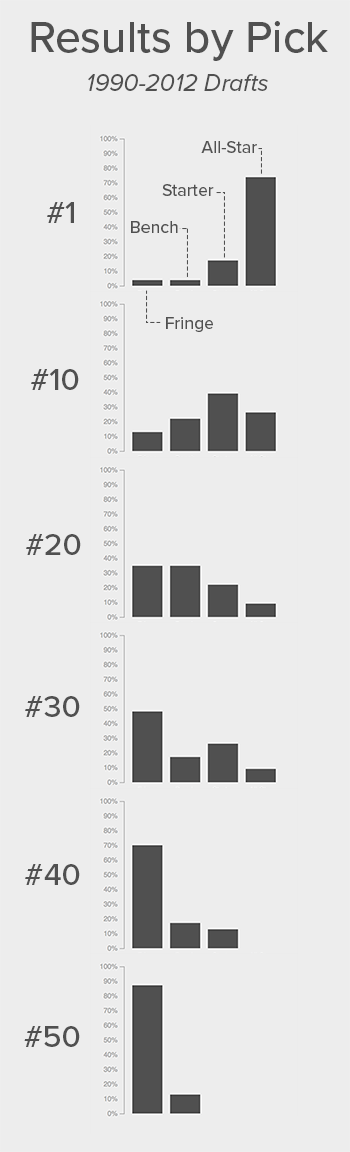

For example, in the 1990-2012 drafts there have been 23 #1 overall draft picks. Roughly1 17, or 74%, have ended up as All-Star level players (think Blake Griffin or Chris Webber). Four have ended up as solid starters or high end bench players (think Andrew Bogut or Andrea Bargnani). One ended as more of a lower end bench player in his prime (Kwame Brown), and one as out of the league (Greg Oden). So we could broadly say that the average #1 pick has a draft risk profile like this: 75% chance of being an All-Star, 15% chance of being a starter or high end bench player, 5% chance of being a low end bench player, 5% chance of being out of the league.2

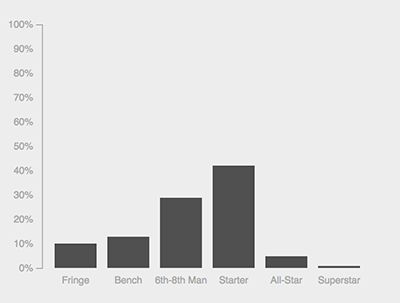

This can be done for all picks, so we can see how an average player picked at any given slot tends to end up:

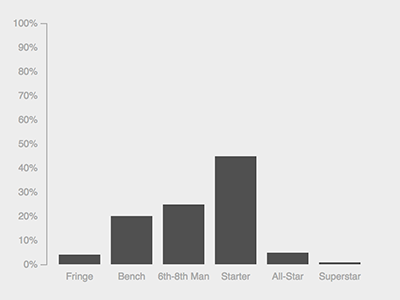

But this isn’t just limited to seeing what happened to players based on where they were picked. We can think of all players in the draft using this same framework, estimating the chance they might end up with any of those outcomes. Some players might be “safer” with less upside, and look like this:

Michael Kidd-Gilchrist might be an example of a “safe” player. Given his overall lack of skill and polish on offense entering the draft, the path to becoming an All-Star was likely much more arduous than for another player picked #2 overall. But given his high character and defensive contributions, it would seem highly unlikely that he’d end up out of the league. So he seemed to have relatively low upside but also relatively low downside.

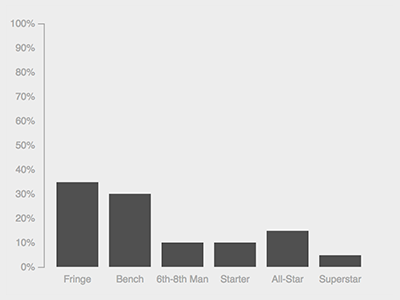

Other players might be very boom or bust and look like this:

Draymond Green might be a good example of this. He was a very valuable college player and demonstrated strong defense and great passing. But he was thought of as a “tweener”, a player without a real position: not skilled enough to play the perimeter but not big enough to play inside. If he was able to overcome that (as he has) he had great potential. If not, he might have ended up like James Johnson or even Julian Wright, bouncing from team to team and maybe not even sticking in the league. The chance he ended up somewhere in the middle as a solid, role playing starter or high end bench player was probably smaller than normal.

Other boom or bust types might be those who, heading into the draft, had personality questions (e.g. DeMarcus Cousins, Larry Sanders, Royce White) or injury worries (e.g. Brandon Roy, Joel Embiid). They have higher than normal downside because of those concerns, but otherwise still have high upside — it’s less likely than for other players that they’ll end up somewhere in the middle of the range of outcomes.

This isn’t anything revolutionary, but it matters a lot — because it fundamentally changes the way we think about the draft.

We’re used to thinking about the draft as a ranking of players. Each team has their own internal draft board that dictates how they select3, and so our conversations about players, both within teams and in the media, tends to focus on ordering players. But player risk profiles don’t lend themselves to a nice order. Two players might have the same average outcome but very different levels of risk. One might be safe and the other boom or bust. How do you rank them? It comes down to the risk tolerance of the franchise and the decision maker. What are their goals, and how much are they willing to live with disappointment if things go against them?

This framework also changes how we evaluate past selections. Often we make judgments of past draft picks based on the outcome of the pick and don’t think about the risk taken. For the teams that passed on Giannis Antetokounmpo it seems clear in retrospect that they made big mistakes. But maybe Giannis was picked at roughly the correct spot at the time given the risk involved? Maybe there was a chance Giannis would become the Greek Freak, and a chance he’d become Yi Jianlian, and teams rightly priced that into his draft position?

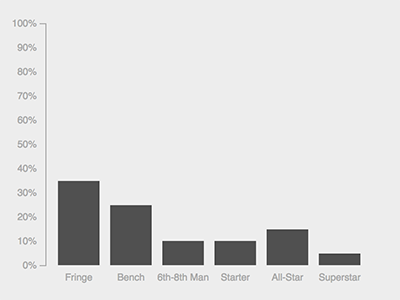

Maybe his profile looked like this:

While Steven Adams’ looked like this:

Does that make taking Adams above him incorrect at the time? Or only in retrospect? I don’t know that there’s a right answer, but it certainly is something that’s not discussed enough when looking back on the successes and failures of team decision making. The risk profile of the player matters.

Risk and Uncertainty

There’s an important distinction to make, though, between risk and uncertainty. In the first two parts of this series I focused on uncertainty, but in this article so far I’ve been talking about risk. What’s the difference?

I use these terms the way they do in economics4: risk is a gamble at a casino, or a roll of the dice. It is a decision made with knowable odds — for example, there’s a 1 in 6 chance the die lands on the number 4. But uncertainty is when you don’t even know the odds, when, as is often the case in life, you don’t have the full picture and you have to make a decision without key information.

The draft is all about uncertainty, and to make a decision it helps to try to transform that uncertainty (whether consciously or subconsciously) into risk — a much more manageable form. But how that transformation happens is crucial, and is an easy place to make mistakes without even realizing it.

In Part 1 I talked about a point Malcolm Gladwell made on Bill Simmons’ podcast. In Simmons’ response to Gladwell we can see an example of the importance of distinguishing between uncertainty and risk. Simmons was discussing what he looks for in draft prospects and mentioned that he feels that players who he’s seen perform at a high level in college in important moments are better picks. “I think when you see [a player make a big shot in a clutch moment in a college game] vs. like the Darko Milicic – oh this guy, if if if, and if this, if this,” Simmons said. “Those are the guys that usually end up getting people fired, the people who look great on paper. I think there has to be some element of you’re already doing it.”

Simmons is saying that players who we don’t know much about (the Darko Milicics of the world who only succeed “if if if”) have very high risk as well as uncertainty. If they haven’t “done it” in a way that is easy for us to see and project then they are more likely than other players to be bad picks. And it’s true: sometimes the less you know about a player the riskier that player is.

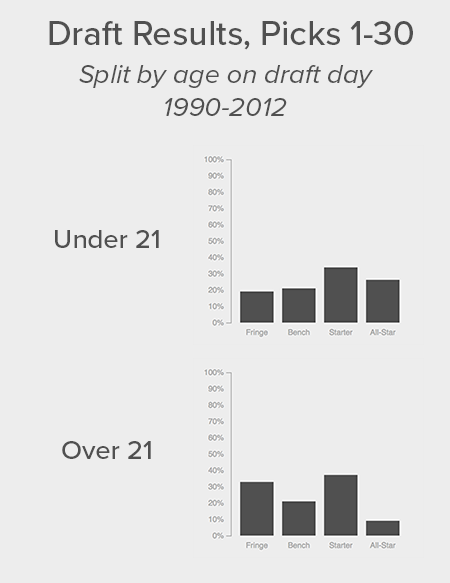

But uncertainty and risk are not always the same. One of the best ways to illustrate this is by looking at age in the draft. The younger the player the more uncertainty is involved: the player is less developed so there is less we know about how they will progress as a shooter or a defender or how their body will change. And yet young players in the draft are actually much less risky than their older counterparts:

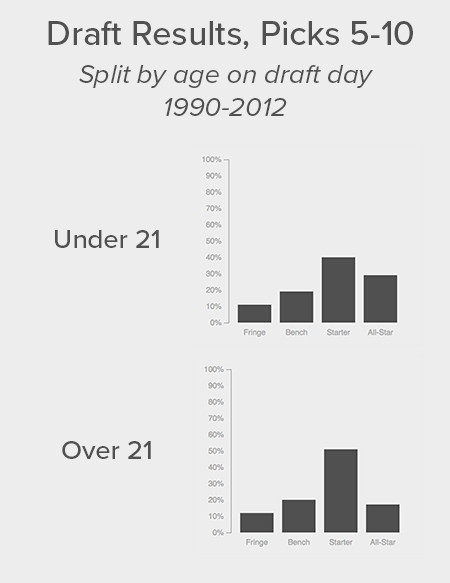

Now, there is some selection bias here: players that are better will declare for the draft earlier than players that are worse, so it could just be that better players are younger in the draft, not that younger players are better. But even if we account for when the player is picked, we see the same pattern. For example, if we look just at picks 5 through 10 (where the younger group is, on average, picked at the same spot as the older group) the results still hold:

The younger players have had higher upside without any higher downside. They are less known, but they are not riskier. But younger players have consistently been drafted lower than these results suggest they should be. They are picked as if they carry more risk because they carry more uncertainty.

A Roll of the Dice

Malcolm Gladwell was right: the draft is random. But not in the way he meant it. Player evaluation isn’t worthless and the selections are much better than just picking out of a hat.

But the draft is a calculated gamble. A gamble where it pays to think in terms of risk and wrestle with uncertainty. A gamble where you have to use all of the tools at your disposal, understand the strengths and weaknesses of human psychology, and lean on statistical analysis when necessary. A gamble where you do all the work you can, get a sense of the probabilities, place your bet, and then roll the dice.

- Placing players in these buckets is a somewhat subjective exercise – you might disagree with some of my decisions. But the goal in this case is not to be precise but to illustrate a general trend. In cases where precision is more important these buckets can be defined more strictly. ↩

- We can, of course, be more sophisticated about how we come up with these numbers, but this is just for purposes of illustration. ↩

- Out of necessity, of course. At the end of the day a team needs to have a list to know which player to pick. ↩

- Technically Knightian risk and uncertainty. ↩