In retrospect there were signs something like this might happen, but nonetheless the layoffs announced by ESPN last week were startling. Some of the most popular and impactful voices in basketball media now need to find another outlet for their work, and for the sake of so many fans, hopefully will soon. The layoffs, though, have another, less direct connection to the basketball world. They are the result of a business model and a changing media environment that has already affected the NBA greatly — and they may be a signal of more changes yet to come.

Cap (Mis)management

At my childhood home we had an ivy-covered hill in between our neighbor’s house and ours. The mailman, following the most efficient route, would walk up that hill everyday, through the ivy, to our mailbox. That saved him from needing to circumnavigate the big ivy patch, but my mother was always annoyed by the unsightly path trampled through the vines. So one day she decided to do something about it. She put up a fence at the end of the path on the top of the hill to block the mailman from getting through.

This would work eventually, but not immediately. The next day the mailman would start along his normal path, through the ivy and up the hill, and only realize his mistake once he got to the fence, forcing him to re-trace his steps. Burned once, he’d hopefully remember in the future — but if there were ever a switch in mailmen the same thing would happen. Because the downside for using the path was so far away from the initial decision it would take someone having learned their lesson once already (or a particularly far-sighted mailman) to avoid going up the hill in the first place.

There’s a certain class of decisions where the results of the decision are significantly disconnected in time from the decision itself. Facing these “mailman problems” it takes someone who’s learned their lesson before, or who has particular foresight, to avoid running into the fence at the end of the path.

Salary cap management is a mailman problem. A bad contract or two won’t often hurt a team immediately — usually, in fact, the team will enjoy the benefits of the newly acquired players and everything will seem fine. It’s only later, sometimes a few years later, when the constraints imposed on the team through overpaying players will tie a front office’s hands. Teams in this situation often seem close to their goals, needing just a little more on the roster to get over the hump. But, lacking the cap flexibility to supplement their current personnel, they bump up against the ceiling of their team’s potential.

The Chris Paul/Blake Griffin/DeAndre Jordan Clippers have been caught in exactly this sort of bind: for multiple years now they have not had the cap flexibility to put an optimal supporting cast around their core trio. With three players taking up so much of the cap, the margin for error has been slim. Filling out the roster properly required developing young players on cheap rookie deals or scavenging below-market contracts or hitting home runs in trades. The Clippers, for the most part, have not been able to do any of the three. They are stuck at the proverbial fence.

The Warriors are an example of the opposite case. Their top-line talent is elite, and perfectly suited for the modern era of basketball, but it’s unlikely they would have put up the best three-year run in NBA history without the contributions of a strong supporting cast headlined by Andre Iguodala. The 2013 Iguodala signing is a perfect representation of what cap flexibility enables: for most teams coming off 47-win seasons a signing like that isn’t even in the realm of possibility. The Warriors needed to trade multiple first round picks to jettison some bad contracts on their books, but they were able to pull it off without sacrificing any part of their core.

How? Because of extreme cap flexibility resulting from some of the best contracts in the league. Here’s an astounding stat: when the Warriors won the championship in 2015, their three best players (Steph Curry, Draymond Green, and Klay Thompson) made less than $15 million combined, taking up less than 25% of that year’s salary cap.1 The Warriors, then, managed to field a roster that included not only those three players but also Iguodala and Andrew Bogut and Harrison Barnes and Shaun Livingston and a vastly overpaid David Lee, all with a payroll that wasn’t even in the 10 highest that season.

The Warriors vs. Clippers comparison isn’t one of brilliant management vs. ineptitude, though. There is plenty to praise in what Golden State has done and plenty to criticize in LA’s transaction history, but the contrasting results might be about timing more than anything else.2 The Warriors signed Steph Curry to an extension after a season in which he played only 26 games due to ankle troubles, giving him security in exchange for getting him on a cap number below what he would have made if he had tested the market the next season. It is the only season in which Curry has missed significant time in his career. Klay Thompson and Draymond Green both broke out while still on their rookie deals — in Green’s case, a second-round contract that paid him less than $1 million per season. Put that together and you get the flexibility that resulted in Iguodala.

The Clippers, meanwhile, never had the chance to build around their three main players when they were on cheap deals. Chris Paul was on a max contract when they traded for him. DeAndre Jordan was already past his rookie deal when Paul was acquired. Blake Griffin’s extension kicked in the year after Paul got there. By Paul’s third season in LA the Clippers’ three stars accounted for almost 80% of the salary cap. Since that point they’ve had a top 5 payroll and not much room to maneuver.

The Warriors are perhaps the most extreme version of this dynamic you could find, but they still illustrate the general point that salary cap management can often be the difference between being good and being great. This may seem straightforward, but executing on it is not — fiscal responsibility requires enormous discipline. There are many factors that push an NBA front office to overspend: a lack of patience, overconfidence in their own talent evaluation, loss aversion regarding their own players, and the winner’s curse, to name a few. Because of that, one of the hallmarks of the best front offices is an ability to effectively manage their cap situation, even (and especially) when it requires tough decisions.

A few years ago, though, something very interesting happened: the value of fiscal discipline almost completely disappeared. This summer the cap will jump to somewhere around the $102 million mark — an increase of $40 million in just three seasons.3 Contracts that at one time might have been a burden on a team’s roster building efforts are suddenly great deals.4

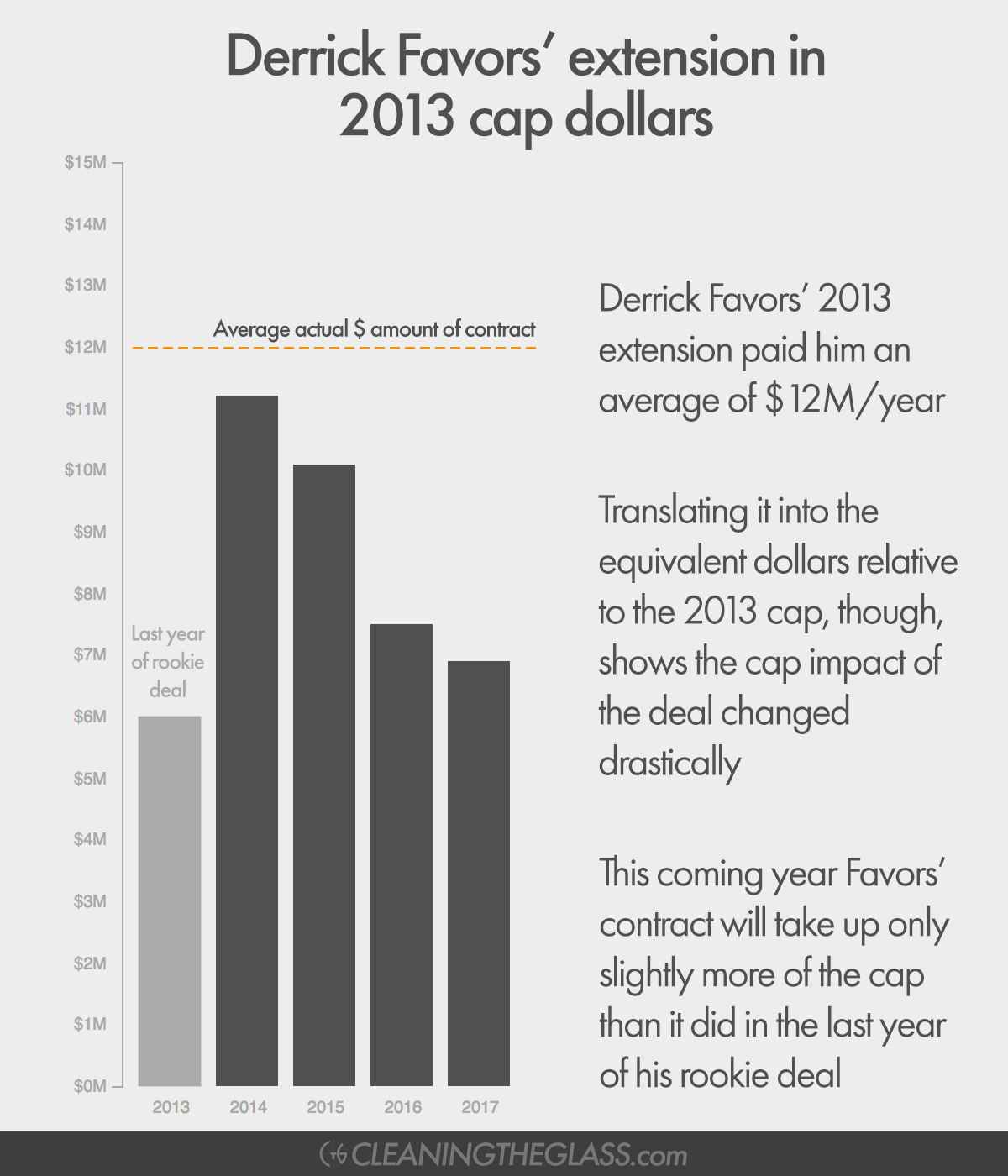

Look, for example, at how the cap impact of Derrick Favors’ extension, signed in October of 2013, changed over time relative to when he signed the deal:

This, oddly, flipped the usual script. Teams that placed a high value on proper budgeting ended up making mistakes, the most notable example of which was Oklahoma City’s handling of James Harden’s extension. At the time, given the cap and luxury tax constraints the Thunder seemed to be facing, one could make a case for not signing him to a market-rate extension. In retrospect, of course, the amount of money they were haggling over is nothing relative to the cap jump.

Teams that seemed to overspend in free agency, on the other hand, ended up with good or great deals, sometimes without even knowing that would be the case. Given the as-yet-unforeseen but impending cap jump, it was almost impossible to sign a truly bad long-term deal. Mistakes were absolved, with no long-term consequences. The flood of new money washed away the sins of cap mismanagement.

ESPN’s Plight

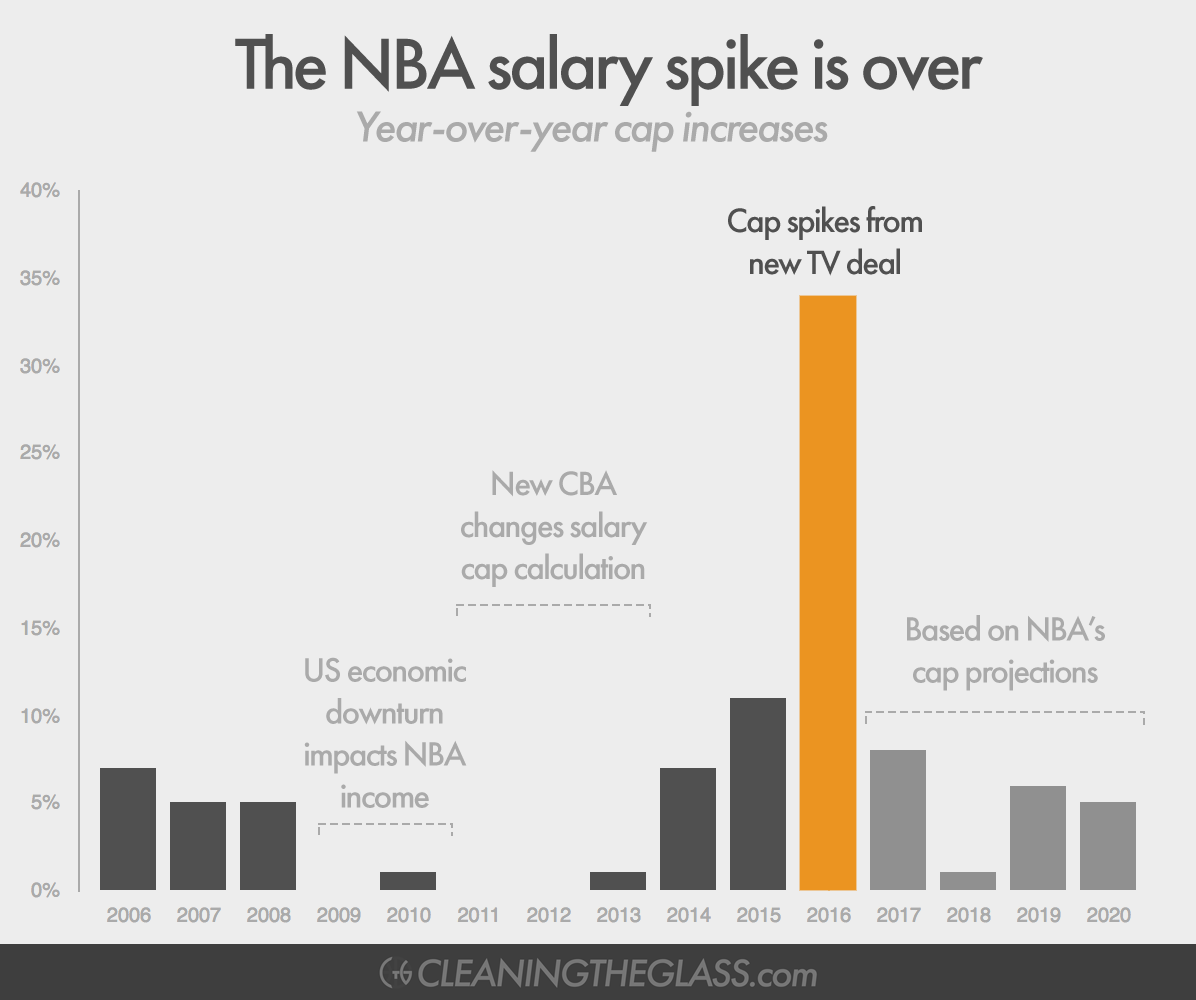

The cap jump didn’t happen in a vacuum, of course. It was driven by the NBA’s new national TV deal, a deal that massively increased the amount ESPN and Turner paid the NBA — from $930 million per year to $2.6 billion. The Collective Bargaining Agreement negotiated between the NBA Players Association and the NBA dictates that the salary cap is pegged to a percentage of how much basketball related income the league pulls in, and with this new TV deal the league was suddenly pulling in a lot more money. Some of that likely has to do with the increased popularity of the NBA, but most of it comes from the realities of a quickly changing media environment.

Live television has been on the decline for some time now. At one point TV was our primary source of in-home entertainment, but the Internet completely changed that. It opened up a variety of alternative ways to spend our time, from streaming TV and movie services to social media. As a result, ratings for TV have fallen almost across the board. The one area that seemed to be mostly resilient to this was live sports, because for sports fans there is no real substitute to seeing the game as it happens.

ESPN realized long ago the attachment sports fans have to seeing the game live, and built their entire business around just this fact.5 Instead of depending on advertising as most other TV networks did, ESPN got the cable companies to pay them. If a cable company wanted to include ESPN in the channels they offered to their customers, ESPN would get a cut. Many sports fans felt the so-called “Worldwide Leader in Sports” was a must-have, perhaps a reason all by itself to sign up for cable. Cable companies recognized this value, and have paid ESPN accordingly: ESPN now receives over $7 per subscriber per month, while no other channel (sports related or otherwise) is even close to that. Most are around or below the $1 per subscriber range.

This brilliant business model made ESPN enormously profitable for a long time, and as recently as 2011 ESPN’s position looked enviable. But technology is changing our consumption habits very quickly, and ESPN has not been immune to those changes: since 2011 their subscriber numbers have tumbled, mostly due to cord-cutting6, from over 100 million to below 90 million. Sports leagues, meanwhile, have realized their value in this new media world and that, combined with the emergence of competition to ESPN from Fox, NBC, and CBS, has allowed the leagues to negotiate from a position of major strength. Take cratering subscriber numbers and mix in spiking sports rights fees and you have a recipe for the public, disruptive, and wide-reaching cuts ESPN made last week.

Though not in the live sports market, there’s a parallel to Netflix’s recent experience here. Netflix’s main business used to be showing movies and TV shows produced elsewhere — using Netflix was the equivalent of renting a movie, a Blockbuster for the Internet age. Netflix paid money to different production studios to license their content and in turn be able to show it to their subscribers. But you may have noticed that’s not really Netflix’s game anymore. Instead they are investing massively in producing their own content. They’ve gone from Blockbuster to HBO.

Why the pivot? Netflix was very early to the streaming game, when the production studios didn’t properly value the digital rights to their catalog of TV and movies. Netflix negotiated a great deal and profited handsomely off of this. But by the time that deal expired the studios had learned their lesson. Combined with other streaming competitors entering the bidding, the costs for that content soared. Sound familiar?

In both Netflix’s and ESPN’s case, the lesson is the same. It used to be that what was important was how we got our entertainment delivered — the networks held real power. But technology has opened up many different delivery options, reducing the value of the delivery service and increasing the value of the content itself. In our current era, content is king.

Netflix reacted to this reality by becoming a content creator rather than merely a provider. ESPN doesn’t have that option. So they have had to pony up in negotiations for sports broadcast rights, the latest of which reshaped the NBA landscape.

Re-Adjustment

There’s a pessimistic case and an optimistic case to be made for the future of ESPN. Clay Travis of Outkick the Coverage makes a compelling argument that we are witnessing the bursting of the cable sports bubble. He (rather vociferously) asserts that the NBA’s TV deal was the peak of sports rights deals and that sports leagues are headed for a wake-up call. Ben Thompson of Stratechery, however, would say that’s an overreaction. Thompson believes that ESPN will successfully double-down on the strategy that has yielded so much success in its history, continuing to pay for sports rights and increasing the carriage fees it charges cable companies.

There is certainly a case to be made that the NBA signed their deal at the perfect time. In 2014, competition to ESPN was just emerging and the network didn’t want to give these other channels the opportunity for any significant sports rights acquisitions. ESPN may also not quite have realized at the time just how much of a free-fall their subscriber numbers were in. Combine that with the fact that the NBA was the only major sports rights deal up for negotiation between 2014 and 2020 and you have the perfect conditions for the NBA maximizing what they could extract from the deal. It’s quite possible that the NBA won’t be able to get quite as good a deal, relatively, again.

On the other hand, the technological changes outlined above all work in the NBA’s favor — after all, they own the content, and content has never been more valuable. Whether it’s to a traditional cable network like ESPN or Fox Sports 1, or to one of the new tech giants who have shown an inclination to jump into sports rights bidding like Amazon, YouTube, Facebook and Twitter, the NBA’s product will hold value to someone. Perhaps, come the next TV deal negotiations, competition will be even more fierce and live sports will have more conclusively proven their unique staying power.

With a real argument to make for each potential outcome, there is a lot of unpredictability surrounding something that has a massive impact on the league. The new TV deal doesn’t expire until 2025, but as we get closer to that date teams will have to think carefully about any contracts they sign that would continue into what could be a very different cap environment.

The cap spike, meanwhile, is finished next summer. After a 34% increase last year and a projected 8% increase this year, the NBA projects the cap to increase just 1% the following season.

As the cap flattens and more of the contracts signed before the cap jump come off the books, the NBA’s financial landscape will change once again. But will front offices re-adjust quickly enough? The same incentives to overpay that have always existed are still there. And now the decisions will be made by a group of executives who have learned over the last few years that you don’t have to pay a price for spending too much. This, as the clock ticks towards the expiration of the new TV deal, with a weakened ESPN casting a shadow of uncertainty over all of it. That well-worn path up through the ivy? Watch out for a fence at the end.

- Numbers from Patricia Bender’s fantastic historical contract site. ↩

- As Nobel Prize-winning psychologist Daniel Kahneman said: “success equals talent plus luck and great success equals talent plus a lot of luck.” ↩

- The salary cap number for this summer isn’t set until the NBA finalizes its books at the beginning of July, so that $102 million cap figure is based on the NBA’s latest projections. Generally the actual cap number isn’t more than $1 million or so off of their latest projection. ↩

- Steph Curry, by the way, is still on that below-market deal, a deal which has become all the more valuable as the cap has spiked upwards. He’ll be eligible for his next deal this summer, but once again, timing played in the Warriors’ favor: Curry hitting free agency a year after the initial cap jump meant Golden State had the room to upgrade from Harrison Barnes to Kevin Durant. ↩

- For an informative and in-depth read on the history of ESPN I recommend “Those Guys Have All The Fun”, an oral history of the network by James Andrew Miller and Tom Shales. ↩

- Or maybe more accurately, cord-never-having, as detailed here. ↩