It starts with the lobs and the layups and the whistles, and if those are taken away, the three-point barrage begins. The launches come from steps behind the three point line, extending defenses beyond their comfort zones. They push the boundaries of what’s been done, the records for three point attempts falling almost as fast as they’re set. Facing this Rockets team, opponents are caught in the ultimate defensive dilemma: protect the basket and face the fusillade of long-range bombs, or stay at home on shooters and take it on the chin at the rim?

The tailor-made trio of James Harden, Mike D’Antoni, and Daryl Morey has brought us the latest step in basketball’s offensive evolution. The way the game is played has been changing as teams and players have embraced the added value of the three point shot — and Houston has been leading the charge.

But this isn’t another article about how the analytically-savvy Rockets crunched the numbers and redefined basketball. Instead, it’s a look at a different team, a team that’s defying this trend and going in the opposite direction: staying big, living in midrange, and playing a seemingly anachronistic style of basketball.

Standing Still is Moving Backward

They play big. They play a halfcourt, methodical game. They’ve led the NBA in midrange shots over the past two seasons combined, ahead of even the Triangular Knicks. Clearly they haven’t gotten the memo that the modern NBA is all about pace-and-space, rim-and-threes, I-can-go-smaller-than-you basketball.

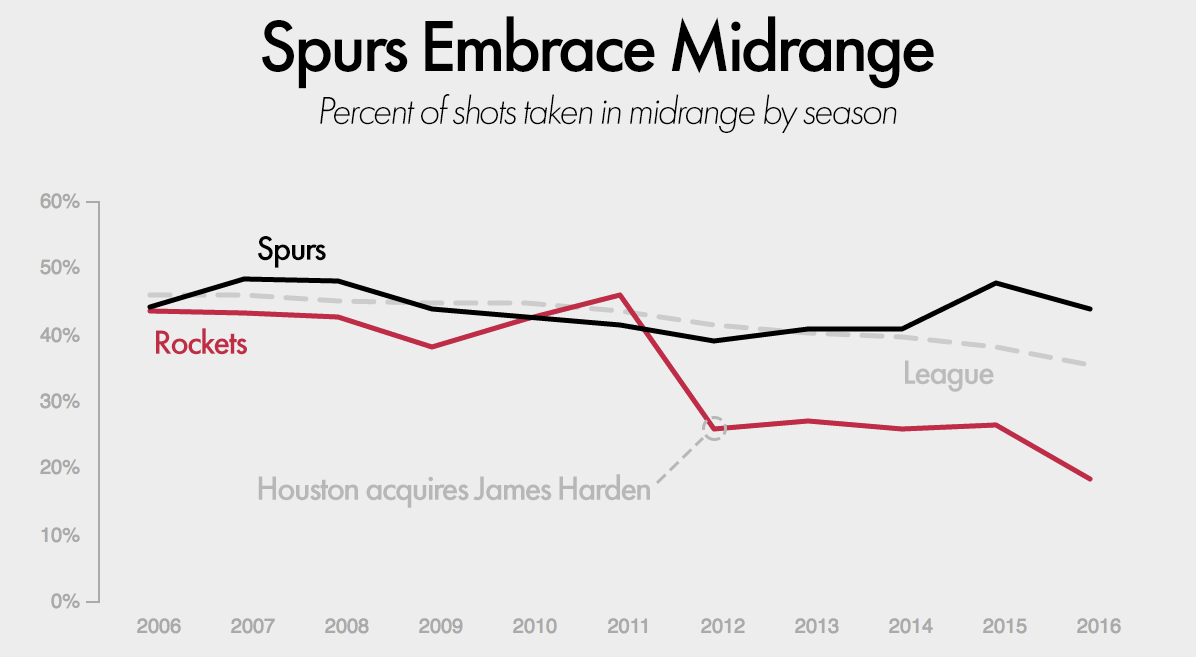

There’s just one small thing to note before grabbing the pitchforks and demanding a change of leadership: in these last two years this team has won more games than anyone but the Warriors. Yes, the Spurs, still in the midst of one of the most successful runs in sports history, have become the anti-Rockets. The movement the Rockets launched after the acquisition of James Harden in 2012 has pulled almost everyone in the league in their direction — except for the Spurs.

It’s not that the Spurs are doing things differently than they have in the past, but that in a quickly changing NBA, standing still is moving backwards. 44% of San Antonio’s shots came in midrange this season, the same percentage as did a decade ago in 2006. But in 2006 that meant 19 other teams took more midrange shots than they did — this year only Detroit did.

Teams have been fleeing the midrange because, when you dive into the data, it turns out most players don’t make long twos at a high enough rate to justify the decreased value of a shot inside the arc. Yet despite the math seemingly working against them, the Spurs have depended heavily on the midrange and still scored efficiently. This year they had the 7th ranked offense and last year they placed 4th. They’ve done it by converting their threes at a very high rate (ranked 1st in 3P% this year, 2nd last year), making the most of the few looks they do get at the rim (8th in rim FG% this year, 3rd last year) and fielding a roster with some of the league’s best midrange shooters. Plus, remember: it’s easier to take care of the ball when you take more midrange shots.

The offense isn’t what propelled them to back-to-back 60+ win seasons, though — it’s the other side of the ball where they’re special. The Spurs have been the best defense in the league each of the last two years, following the same formula they have for almost 20 years: protect the rim, don’t give up threes, don’t foul, and don’t let teams beat you in transition. Their defense, then, is perfectly suited to stop these modern, Rocket-fueled offenses.

There’s something confusing about this, though. If the Spurs get the math on one end, how does it not transfer over to the other? When their defense forced the most midrange shots in the league last season, their offense also led the league in midrange shots attempted1. The same question could be asked of the Rockets, in reverse. How can they treat midrange shots as offense-killers on one end, but rank in the bottom half of the league in forcing midrange shots in each of the last three seasons on the other end?

There’s something deeper going on here than stylistic preference. Something that cuts to the heart of almost all current basketball debate.

Size Matters

Basketball, perhaps more than any of the other major sports, is about trade-offs — there are tensions inherent to the game, and they pop up in a variety of coaching and roster decisions. I covered one of the more overlooked trade-offs, between turnovers and shot selection, in “Do the Bucks Stop Here?”. The trade-off between offense and defense is a little more apparent, but still often goes underemphasized. Whether in coaching schemes or in personnel decisions, to get what you want on one end of the floor almost always forces you to give up something on the other.

This, I believe, is what’s going on with the Rockets and Spurs — they are attempting to optimize different sides of the ball. For the Rockets the question is: how can we play the best defense possible given the style of offense we want to play? And for the Spurs it’s just the opposite: they are a culture of defense, and start their decision-making from that perspective.

This manifests itself in many ways, perhaps none more important than in who is on the roster and how they are used — particularly at the big man positions. The Spurs played almost 80% of their possessions with two traditional big men this year, which led the league. The Rockets, meanwhile, played fewer than 1% of their possessions this way, one of three teams this season to play big that infrequently.

We can look at this for the whole league, breaking down lineups into three categories: how often they played “big”, how often “spread”, and how often “small”. A “big” lineup would be one with two traditional big men, those who don’t shoot many (or any) threes and have real size. A “small” lineup is one where the player playing power forward doesn’t have the height or weight to be considered a true big man, and is likely someone who usually plays on the wing. And a “spread” lineup is one where the power forward is the size of a normal PF but can also shoot threes.2

If we look at how teams tend to play with these different types of lineups on the floor over the last 5 years, we find some interesting results:

| Offense | Defense | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lineup Type | % of time | Pts / Poss | % Midrange | Pts / Poss | % Midrange |

| Big | 42% | 106.1 | 43% | 106.1 | 41% |

| Small | 19% | 107.9 | 36% | 108.8 | 37% |

| Spread | 39% | 108.7 | 36% | 107.4 | 38% |

This fits our expectations, and what we’ve been looking at with the Spurs and Rockets. Big lineups have been worse on offense and have taken a higher rate of midrange shots than either their small or spread counterparts. But they’ve also been very good on defense, and forced more midrange shots than the other lineup types. Again: to get what you want on one end of the floor forces you to give something up on the other.

You hear it a lot in the media these days: it’s so hard to go big because your spacing isn’t ideal — good defensive teams will clog the paint and force you into low percentage midrange jumpers. But you don’t hear the other side as much, as important as it is: go small and good offensive teams will attack you in the paint and on the glass, as the Spurs did (after settling for some jumpers early) in Game 5 when the Rockets played Ryan Anderson at center:

Of course it’s not only a choice between these two extremes, between being the Spurs and being the Rockets. There is a middle ground, and it’s in the lineup type that has the best point differential of those listed above: trying to take more traditional big men and develop enough of a three point shot that they can become spread bigs. A big man who can also shoot is the best of both worlds. The Spurs have shown signs of heading this direction with Pau Gasol, who attempted the highest rate of three pointers in his career this season (though it was still a relatively low rate). And it might be something they look to do with LaMarcus Aldridge in the future.

Pushing midrange shooting big men out beyond the three point line is responsible for much of the three point shooting increase we’ve seen in recent years. If we compare the numbers in the table above to the ones from the previous 5 seasons (2007-2011), we find that teams are not actually playing small any more than they used to, despite what you may have heard. Instead, 16% of the possessions that previously went to big lineups now go to spread lineups. Some of this is coaches changing which types of big men they play, but the vast majority of it is big men who previously would not take threes expanding their range.

When I first started with the Trail Blazers in 2008, Channing Frye was in his 4th season as an inefficient, jump shooting big man. Every year 60% of his shots would be long midrange jumpers, and while he’d make a decent rate, it’s hard to be an efficient player and a positive offensive contributor taking that many long twos. It seemed like he might have three point range in practice, but that wasn’t enough for the coaches to let him take threes in games. Someone like Frye shooting threes was viewed as bad offense, an unreliable shot, and a player straying from what they do well. It’s a view that, just 9 years later, seems downright archaic. Now Frye launches 60% of his shots from three, is one of the most efficient big men in the league, and makes his team much better on the offensive end through the spacing he provides.

The problem is that finding a big man who can both space the floor and defend at a high level is very difficult — most of the best shooting big men also happen to be underwhelming defenders. If you don’t have one of those rare few who can play both ends of the floor, what do you do? The public dialogue has made it seem like going small is the only choice, the inevitable outcome in a league increasingly enthralled with shooting.

But basketball is a complex puzzle, not easily solved with simple prescriptions. The Spurs prove that the answer isn’t always “go small and shoot more threes”. As has been true since the invention of the game, size matters.

Spurs vs. Rockets

This series, then, is a clash of extremes: of big vs. small, of offense vs. defense, of old vs. new. What happens when these two extreme styles play each other? Which wins out? That’s a complicated question and requires a suitably nuanced answer, one that is best saved for an article of its own.

Whichever team wins this series, we shouldn’t draw some sweeping conclusion about what works or doesn’t in the modern NBA. The fact that both of these teams are even here is testament enough to the idea that there is more than one way to win. Still, watching the Rockets and Spurs go back-and-forth in these games, it hasn’t just felt like two teams battling. It’s felt like two eras.

- Interestingly, the Pistons accomplished the same dubious feat this season: they led the league in midrange shots forced on defense but also midrange shots attempted on offense. ↩

- There is no perfect way to split these players up, but here is how I ended up doing it. A small PF is one whose listed height is less than 6’10” and whose listed weight is less than 230 lbs. A big PF is one who is either 6’10” or taller or weighs more than 230 lbs. and attempted fewer than 2 threes per 36 minutes that season. A spread PF is anyone else: basically someone who is bigger than the “small” cutoffs and takes a lot of threes. ↩